Artificial intelligence a metaphor for a lot of computational processing. It’s not just one specific thing, but a lot of different things. Often we hear about “AI” as a blanket term for all sorts of stuff. One summary of the challenge differentiating various forms of AI is as follows: “AI is a flexible, ambiguous, generalized term whereas Machine Learning [ML] is a set of computational techniques for accomplishing specific tasks with a large amount of data. AI has associations with grant funding, too, and tends to be more of a marketing term with fanciful associations, such as with the movie The Terminator.”[1] But there are specifics to what is going on under the hood here.

Machine learning is a series of computational processes primarily designed for classification. Machine learning, simply put, follows the maxim of If this happens, then do that. These kinds of commands can be fine-tuned and adjusted to perform differently based on need, appropriate response to input, etc. Machine learning outcomes can be supervised (guided by input) or unsupervised (left to run on its own to find patterns). Both are equally useful and have their own benefits.

However, Generative AI is NOT specifically looking to fine-tune. Given the world of what is known to the model, we are asking the computer make the best guess! Instead of trying to classify outcomes, generative models ask: How likely is this outcome given everything else that has already happened? And, if you don’t like your answer, you can try again by prompting it again.

What does that mean in practice?

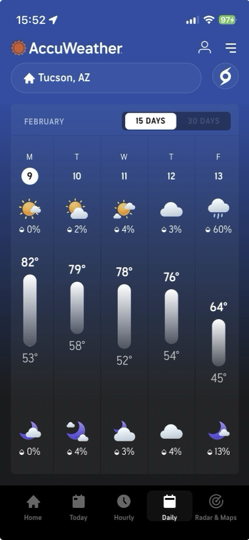

Artificial intelligence (all of it, no matter what you call it) relies on probability, which is a measure of how likely it is that a thing is going to happen. One example of this is rain: Technically speaking, every day there is a 50% chance of rain: it could rain, or it could not. However, unless you also lived in Scotland, you know that is not really a realistic expectation for weather reporting. When we talk about probability, we are measuring on a scale of 0-100:

0% = not likely

50% = could go either way

100% = definitely going to happen.

This can be considered a continuum — A 60% chance of rain does not guarantee it’s going to rain, but it is higher than 0%, 2%, 4%, 3%, etc seen in the daytime between the week of February 9-13 in my weather app, seen to the left. In other words, it is more likely that it will rain on Friday than it is the rest of the week, but it doesn’t guarantee that it will definitely happen. And you can combine that with other possibilities: If it rains, how likely is it that we’ll have clouds? What about the likelihood of flooding?[2] How likely are leaks? What about cats and dogs falling from the sky? These kinds of aggregational probabilities help us understand what is possible and make informed judgements.

Let’s look at two examples of this in action.

Menstrual cycles are, on average, 28 days long. But not all women’s[3] cycles are 28 days long – some women are on a 25 day cycle, some of them are on a 30 day cycle, etc. (For those of us who are interested, these differences represent standard deviations from the stated average norm.) But we can apply machine learning and generative AI models to period tracking and see what they look like in practice.

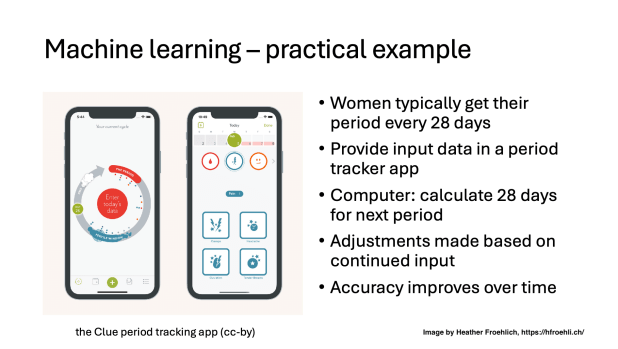

Figure 1: Machine learning – a practical example

The default starting input for all period trackers is to calculate 28 days from the start of your last cycle. Let’s pretend your cycle is 30 days instead of the average 28 days. The initial 28 day notification is close, but not quite there. But, as you keep giving your period dates to the app, it will start to adjust to your next period dates accordingly. In a machine learning model, accuracy improves over time: it eventually will accurately predict your 30 day cycle without you doing anything beyond simply giving it more data.

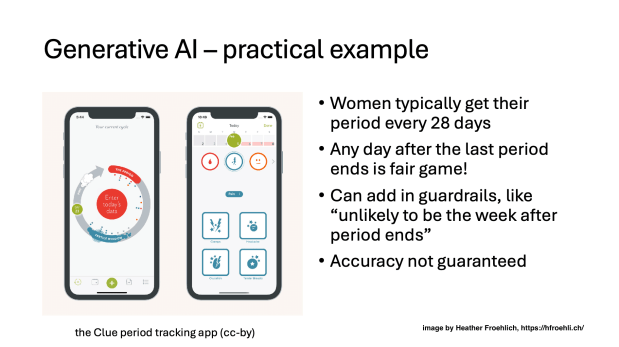

Figure 2: Generative AI – a practical example

As before, the default starting input for all period trackers is to calculate 28 days from the start of your last cycle. But in a generative system, anything can happen after your last period ends! All we know is that it can start any day in the next 28 days. Women who menstruate know that this is definitely not correct, and depending on the random dart landing on the correct day under this model is not very reliable. Of course, someone could program a generative period tracker with the detail that “it is unlikely to be the week after the last period ends”. That still leaves 2 more weeks of potential dates for a period to arrive, and any of those dates are still fair game.

Using probability, both models are trying to guess when your next period will be. If the generative model happens to be right, that’s good, but it’s definitely not a guarantee in the same way that the machine learning model figures out your cycle and adjusts accordingly. The next question I always get, then, is why does genAI give me a wrong answer so confidently? The answer is buried in figure 2 above: each day is equally likely to be a next period, so any of those outcomes are potentially viable. We know more than the generative model, so relying on it for facts is maybe not the best idea.

[1] Gallagher, John R. “Lessons Learned from Machine Learning Researchers about the Terms ‘Artificial Intelligence’ and ‘Machine Learning.’” Composition Studies 51, no. 1 (2023): pg 149.

[2] In Tucson it turns out the likelihood of flooding with rain is pretty high, especially in the monsoon season – more so than anywhere else I have lived. It’s part of the floodplan for the city.

[3] I am aware of the implied gender essentialism of this piece; I tried writing “menstruating people” a great number of times and found it challengingly wordy in this post. Clue, the app I include in the images here, is particularly good at keeping their content gender neutral. See https://helloclue.com/articles/culture/accessibility-gendered-language-at-clue as an example.